As I sip on my first cup of coffee while sitting in my backyard, I enjoy the most beautiful concert of praise from the birds that frequent my backyard: cardinals, orioles, mockingbirds, jays, wrens – each having their own distinct song. Not only do they know how to make meaningful sounds that attract the opposite sex, warn off intruders, or train their young but they instinctively know how to identify their meaning. How brilliant our creator God was when he molded something in each bird family that bestowed on them an innate knowledge of their own distinct song(s)! As I contemplate the wonder of it all, I can’t help but ask: Do they teach their young? Why do they know the sound of their own family? Why do they know the meaning of each sound?

God gave mankind the unique gift of language, communication through words, to express our thoughts, our knowledge, our hearts. He provided us with the capacity to use it for creative thought (Griffiths, 2014). After all, building relationships through communication is one way humans are distinctly different from the animals He created. If such knowledge is built right into the fabric of the essence of birds, would it also not be true that our Creator would give His Image Bearers the inner ability to speak a language before we were taught to speak by our parents?

Thus began a journey of inquiry on my part. I began to read what linguists said about language development, As I studied, it became clear that research supports the fact that the ability to speak and understand is innate – that is, inborne. In other words, humans are born with the capacity to learn any language and even understand language before they first born (Brynie, 2010; Mccarthy, 2020). Research supports the capacity for language developed in the infant brain before birth. In fact, newborns are “wired” to understand and speak any language. According to a study published in the National Academy of Science, linguistic principles that are active in all human brains are present at birth (Gomez, et.al, 2014). Human babies instinctively grasp the structure of any language, confirming that humans, but not animals, were created to speak (AIG, 2016).

You are probably asking yourself, “What does our inborne ability to develop language have to do with electronic devices?” Put simply, in order for these innate abilities to develop into language skills, there must be interaction with other humans. Parents provide an important role by talking to their children…The bottom line is, if infants are not spoken to, they cannot acquire language. According to the Linguistic Society of America, there must be interaction – not only with parents but with other children and adults (Cowie, 2017).

In a longitudinal study (scrutinizing the same individuals over a period of time), 894 children between the ages of 6 months and 2 years found that by 18-months, 20 percent had daily average handheld device use of 28 minutes, according to parents. Based on a screening tool for language delay, there was a direct correlation between handheld screen time and increased risk of expressive speech delay; in other words, children have a hard time providing information using speech as well as other forms of communication such as writing when they enter school. Furthermore, for each 30-minute increase in handheld screen time, researchers found a 49% increased risk of an expressive speech delay (AAP, 2017). Research conducted by linguists in the United States, India, Malaysia, and Canada concluded that “Infants with more handheld screen time have an increased risk of an expressive speech delay” (Operto, et. al, 2020). Studies also show receptive language (what we understand) and pragmatic language (social interaction) are delayed due to electronics (Alvarez, 2019).

Why? The number of words babies and toddlers hear is correlated to better language skills, but this must happen on multiple levels – taking in words, vocal intonation, gesture, facial expressions, forming words – electronic devices do not do provide these multilevel language experiences that are needed to develop speech. Electronic devices do not mediate for your child in a world that requires human interaction for wholeness of body, soul, and spirit.

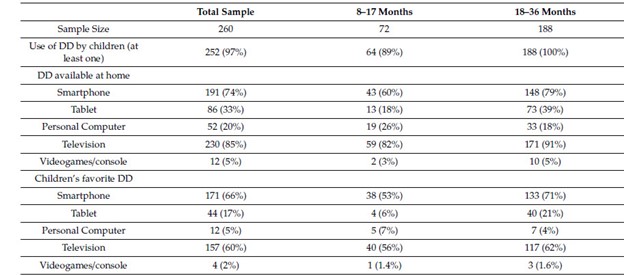

Table 1. Digital Devices Questionnaire (Operto, et.al, 2020)

Table 1 shows the reported availability and use of digital devices for children 8-36 months in 2020; these numbers are on the rise adds to the complexity of this issue. The more time a young child is exposed to screens, the less time he is exposed to verbal exchanges that help promote language skills and communication development. Recent research showed that children exposed to TV screens during family meals had a lower verbal IQ at age 2 (Martinot, et. al., 2021). Even with more extended background television children had weaker language skills (Mandal, 2020).

In order for innate language abilities to develop into language skills in a child, there must be interaction with other humans.

The number one predictor for success in language is talking to your children. Why? Because our ability to understand and communicate a language is attained knowledge – learned from others (Cowie, 2017). In order to learn to talk and communicate, interactions with others during their first few years of life are crucial for the child’s language development. The more time children under 2 years old spend playing with smartphone, tablets and other handheld screens, the more likely they are to begin talking later. Every minute your child spends in front of a screen is one fewer minute that he could spend learning from interactions and practicing his engagement with you. Screen time takes away from time that could and should be spent on person-to-person interactions.

Encouraging Language Development in a Digital Age

God gave us instructions telling us when to teach our children: “You shall teach them to your sons, talking of them when you sit in your house and when you walk along the road and when you lie down and when you rise up” (Deut. 6:7; 11:19). God’s instructions: Parents are to talk about His precepts 24/7 because persistent instruction is how parents instill attitudes, ideas, and skills in handling life through a biblical lens. A Hebrew child’s first words were the Shema found in Deuteronomy 6:5-7 which was repeated every morning and evening. God, the one who created us, knew that it was important to communicate with a child to give him an understanding of the language and the ability to communicate.

If you want to improve your child’s IQ, turn off all the digital devices (screen time) from ages 0-36 months! Background noise even affects the development of your child’s language skills. YOU are your child’s babysitter, caretaker, and teacher. BUT don’t develop a guilt complex, especially since the idea of NO digital devices is impossible. Here are some things you can do to help your child develop language skills:

- While in the car, talk about what you see along the road. Using a digital device should not take the place of conversation or discipline. Sing, learn poems, engage with your child, play games like, “I see a red car. What do you see that is red?” Awareness of the environment around you is a great instructional tool When my kids were growing up (even though it was a million years ago!), traveling in the car was one of the best parts of the day because we talked about what was going to happen or what had happened during the day. . . we use words to communicate with each other.

- Talk to your baby/toddler. Research shows that the more you talk to your 0–3-year-old, the sooner they develop language skills. So, talk continually. Respond to your child’s cooing and verbal responses by smiling, even if you do not understand. Acknowledge and praise their responses!

- Build language face-to-face using expression and body language. Smile a lot; use gestures and inflection when you speak. Indicate emotion with your voice – excitement, seriousness, asking questions, etc.

- Mom, why are you using a screen? Talk about and show your child why you are using technology. For example: Are you looking up a recipe? Finding activities for the weekend? Loading a resume? Show them, talk to them about it. You are training them to consider electronic devices as tools much the same as using a cookbook, the newspaper, snail-mail, etc.

- Read a story together. Engage your child in conversation by asking questions and making comments. Even if they cannot give you answers in full sentences, their one-word answers suffice. Repeat their answers in complete, grammatically correct sentences so they learn language skills.

- Talk continually explaining things, asking questions, and engaging your child in conversation. There is one piece of science that is the biggest predictor for success in language, and that’s talking to your children. Connect what you see and hear to your child’s everyday experiences. Children need to hear the language before they can use the language. It is a fallacy to think you can only use the language they have already mastered or that is age-level appropriate – that innate ability helps them understand the smartest thing even before they can say them (Lang, 2018). They need to hear new words to develop language skills and build their vocabulary.

- If your child has screen time, watch it together. Using digital devices should not be used for entertainment unless it is spent in time together. Be sure to select high-quality programs. Talk about screen time as you watch it together. Watch a portion (15 minutes a day) of a video or movie and talk about it. Use the language in the video as you talk so your child learns new words; you are building language face-to-face. Talking about what you observe in short sessions help with long term memory and picturing in your mind, an important aspect of training for cognitive memory.

- Play with your child’s toys with him. Talk as you play. Use imagination and pretend. Remember that three-dimensional toys are tangible

and help your child learn concepts like size, texture, quantity, etc. whereas pictures and digital devices do not even come close. Explain; question; build those all-important concepts so talk to him about ideas. “This animal is an octopus. How many arms does it have?” (count with him) “What color is the octopus?” “What color is his tongue? are his eyes?” “Did you know that real octopuses are not this color?” (explain) “Is he happy or sad? How do you know?” “Which one of the rings is round? A star? A fish? A crab?” “What color are the rings?” Play a game with this toy and talk about it while you play: “I am trying to throw the green star onto the octopus’s arm. Do you think he can catch it? What are do you see yourself doing?” Your child tells you in complete sentence; repeat in a complete sentence with correct grammar…And so on.

and help your child learn concepts like size, texture, quantity, etc. whereas pictures and digital devices do not even come close. Explain; question; build those all-important concepts so talk to him about ideas. “This animal is an octopus. How many arms does it have?” (count with him) “What color is the octopus?” “What color is his tongue? are his eyes?” “Did you know that real octopuses are not this color?” (explain) “Is he happy or sad? How do you know?” “Which one of the rings is round? A star? A fish? A crab?” “What color are the rings?” Play a game with this toy and talk about it while you play: “I am trying to throw the green star onto the octopus’s arm. Do you think he can catch it? What are do you see yourself doing?” Your child tells you in complete sentence; repeat in a complete sentence with correct grammar…And so on.

Have fun relating to your child . . . these first 3 years are the formative years and the time you spend with them is most important. I would love for you to share ideas on how you increase your child’s language skills without using digital devices.

References:

AAP. Handheld Screen Time Linked with Speech Delays in Young Children. Pediatric Academic Society. May, 2017.

Alvarez, Mandy and Melissa Marinelli. Screen-Time Is Linked to Language Delays. Parents, BabySparks On-Line, 2019. Retrieved from https://babysparks.com/2019/02/12/screen-time-is-linked-to-language-delays/on 9/15/2021.

Answers in Genesis, “Deaf Babies Show We Are ’Created to Speak’” Creation, 18, no 3 (June 1996): 49.

Brynie, Faith. “Infant Brains Are Hardwired for Languages,” Psychology Today, February 19,2010. Retrieved from http://Psychologytoday.com, on 9/2/2021.

Cowie, Fiona, “Innateness and Language,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/innateness-language

Gomez, D. M., I. Berent, S. Benavides-Varela, R. A. H. Bion, L. Cattarossi, M. Nespor, J. Mehler. “Language Universals at birth.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2014; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1318261111

Griffiths, Sarah. “Language is a ‘biological instinct’: Babies don’t learn to develop speech – they’re BORN with the ability,” April 9, 2014.

Mandal, Ananya. Screen Time Impairs Children’s Language Skills, March 23, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.news-medical.net on September 6, 2021.

Martinot, Pauline, Johathan Y Bernard, Hugo Peyre, Maria DeAgostinin, Anned Forham, Marie-Aline Charles, Sabine Plancoulaine, & Barbara Heude. “Exposure to Screens and children’s language development in the EDEN mother-child cohort,” Scientific Report, 2021, 11:11863.

Mccarthy, Laura Flynn. “What Babies Learn in the Womb”, Parenting 2020. Retrieved from https://www.parenting.com/baby/what-babies-learn-in-the-womb/#:~:text=Perhaps%20the%20most%20significant%20one,actually%20recognize%20their%20mother’s%20voice. On 11/2/2022.

Operto, Francesca Felicia, Grazia Maria Giovanna Pastorino, Jessyka Marciano, Valeria de Simone, Ana Pia Volini, Mariam Olivieri, Roberto Buonaiuto, Luigi Vetri, Andfrea Viggiano, and Giangennaro Coppla, “Digital Devices Use and Language Skills in Children between 9 and 36 Month,” Brain Science, 2020, 10, 656.

engageny.org

engageny.org

Share this entry